The invisible tyranny of history

“If we could have done it this way from the start, we never would have done it any differently.”

That’s what a physician colleague of ours remarked after trying an early prototype of our product. It was an interesting statement. It acknowledged that what we’ve designed wasn’t possible before. And it was an admission that the way we’ve all been interacting with medical images to-date was needlessly painful in a way he was previously unaware.

It made me ponder a question: Is there a word that means something being the way it is for no good reason other than the sequence of historical conditions that preceded it? A condition that describes things that made sense given past conditions that don’t make sense anymore with new contemporary options?

Anachronistic Inheritance

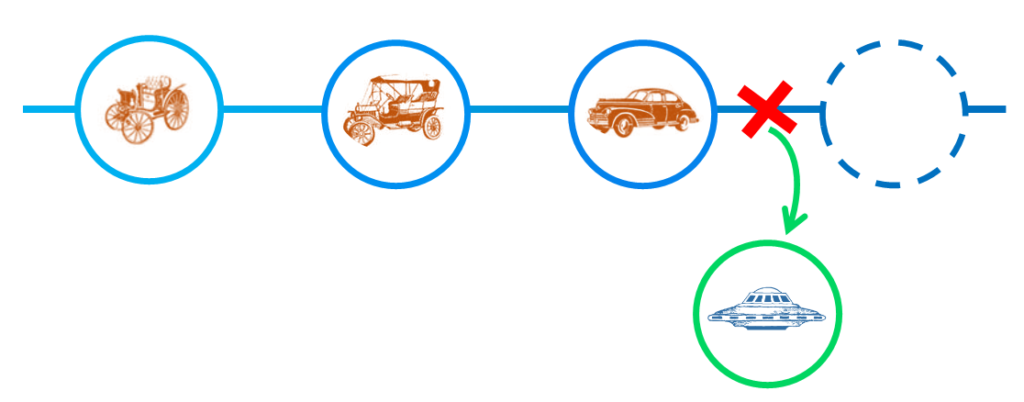

I couldn’t find a word, so I came up with the term “anachronistic inheritance”. Inheriting the historical conditions that are now anachronistic. The concept describes something that made sense given historical conditions but is no longer optimal – or even worthwhile – given contemporary options.

It’s difficult to come up with examples that illustrate the concept, since by its nature we’re usually blind to it until we’ve been shown something better. However, many significant innovations seem to be characterized by a departure from anachronistic inheritance:

- The iPhone removing physical keyboards

- Uber departing from the concept of taxis

- Amazon and the Kindle changing the way we buy and read books.

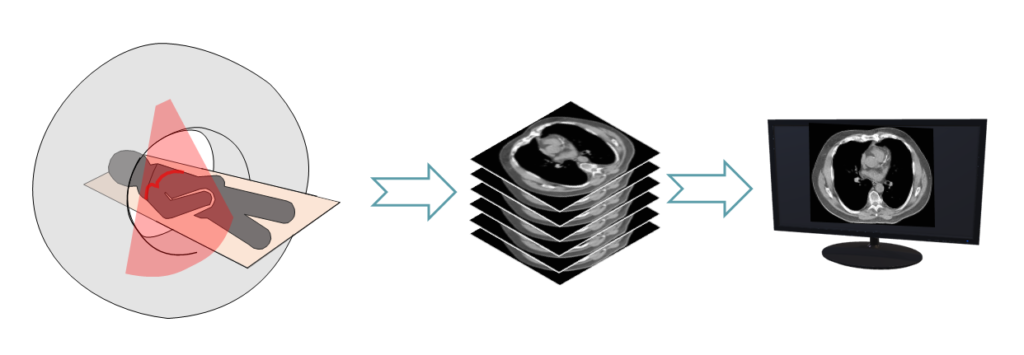

A necessary condition of the concept is a new technology (or collection of technologies) that enables previously unimagined solutions. Afterall, before the change in technology (touch screens for the iPhone, ubiquitous internet and GPS connected devices enabling Uber, the internet and e-ink changing books) the entrenched solution just made good sense. We wouldn’t have been using it otherwise! With medical images, a good example is treating volumetric images conceptually as stacks of 2D slices since (a) that’s how the images were historically acquired with fan-beam tomographic CT scanners, and (b) the only good way we had to view them given our reliance on 2D monitors.

Many significant and game-changing innovations seem to be predicated on a strong departure from anachronistic inheritance. Someone could have taken the technological changes that enabled Uber (internet and GPS connected devices) and made an improvement to the taxi industry itself. By departing from the history of taxis, rather than adding to the historical progression of them, Uber found a solution with significantly more value. The lesson: creative innovators can likely find greater benefit out of new technology by radically re-examining what we all take for granted as “the way things are done” in order to uncover valuable and behaviour-changing solutions.

Virtual reality destroys historical assumptions

At our company, we’re energized by the possibilities that VR brings to this creative re-examination process. Beyond being an immersive and powerful tool for 3D visualization, VR enables the creation of workspaces entirely unfettered by real-world constraints (only your imagination). With such versatility, it promises to enable many new ways of performing tasks or solving problems, making previous form-factors and historical conditions outdated in the process. That said, the ground-breaking solutions it holds aren’t guaranteed.

Two types of gimmick

Even before the modern resurgence of the technology, applications of virtual reality have had a long history of being labelled as “gimmicks”. And often for good reasons! The concept of anachronistic inheritance helps to identify the two ways that gimmicks are created. I’ll explain with examples of VR applications in radiology.

Gimmick #1: The underwhelming increment

Modern radiology work stations are commonly found in the form of several high-resolution computer monitors in a dimly lit room. Volumetric images are viewed slice-by-slice in 2D on these monitors. An example of creating a potential gimmick is using emerging modern VR tech to recreate this exact form factor. The benefit, in this case, would be flexible and customizable workspaces. I like to describe these types of solutions as: “Doing what we’ve always done… but in VR!!”

Another example in radiology is VR or augmented reality being used only to view the medical models that we’re already 3D printing. There are significant benefits to removing the physical constraints of physically printed models, but there’s a vast space of creative possibilities in VR that are left unexplored if that’s where you stop.

It’s underwhelming to see a powerful new technology being used to incrementally improve the historical lineage of a solution. And not only does the minimal improvement fail to motivate a change in behaviour (in this case, working in a headset instead of in front of a monitor), it gives cynics the ammunition to dismiss the enabling technology itself: “VR? I don’t really see the point.” The underwhelming increment fails to define an anachronistic inheritance and then depart from it.

Gimmick #2: The poorly motivated radical change

The opposite way to create a gimmick is to create radical change for its own sake. This tactic is the pitfall of the visionary or enthusiast. You’re so excited about the new possibilities of VR that you want to change every aspect of a particular task, throwing the baby out with the bathwater in the process. A good example of this is an application that focuses exclusively on 3D volume renderings of CT scans*. Reactions to such applications come in two flavours:

- “This technology is going to change medicine!” and,

- “That’s cool but I really don’t see it being used clinically.”

*Looking at volumetric images in full 3D has some valuable benefits, but it forgets that, primarily, when a radiologist or other clinician is looking at images, they’re using the image grey values themselves as a reference only, and not as clinical truth. The grey values of the image are inherently ambiguous (“is this a blood vessel or a lymph node?”), and the task of the viewer is to use their clinical knowledge to disambiguate the features. Volume rendering relies exclusively on those grey values to create 3D structures: it’s skipping right to the end while removing the crucial clinical disambiguation.

I react more favourably to gimmick #2 because it’s on the right track. It recognizes the possibilities enabled by VR and departs from the historical lineage. Where it fails is in finding the useful and valuable solution to the actual real-world problem being tackled. It results in excitement without any actual engagement.

Finding the answer

The answer to look for, the solution that destroys the historical lineage while also providing the usefulness and value, is somewhere within that creative space in between underwhelming increment and unengaging excitement. That’s why we spent and continue to spend a lot of time playing with interesting ideas and trying to test our basic assumptions.

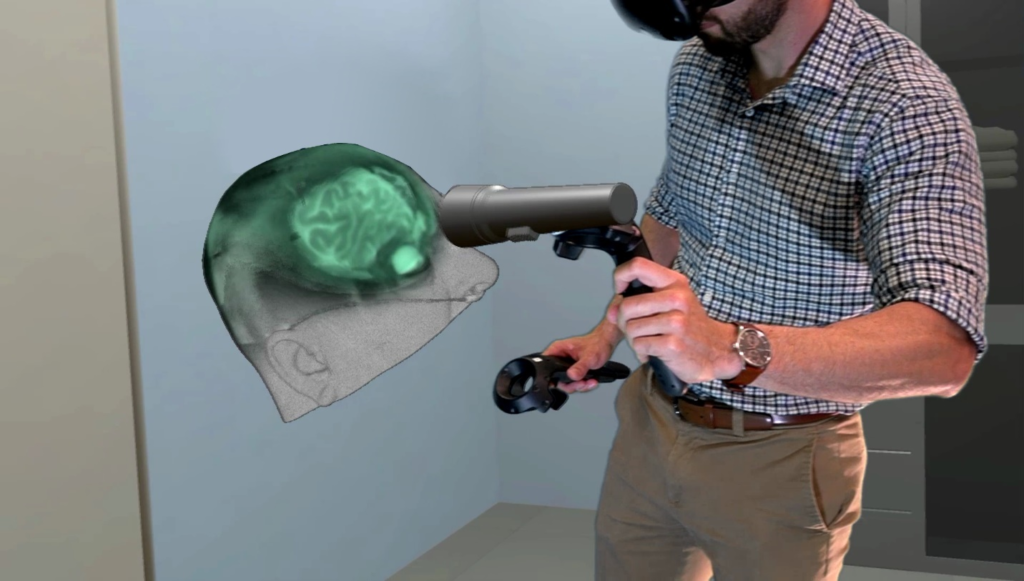

It’s how we came up with the idea of the x-ray vision flashlight, by asking ourselves the question “How would Superman’s X-ray vision work in practice, and what does that look like?”

The x-ray vision flashlight: revealing a fused T2-weighted MRI beneath a 3D rendered CT scan

While flashy, we knew full well that it was an example of gimmick #2: that the x-ray vision flashlight didn’t have any actual clinical utility. Nevertheless, we still made sure to show it to every physician collaborator we interacted with. Who knew where their resulting ideas might lead us when they were shown a world untethered by the past – when they started departing from anachronistic inheritance in their own thinking? At what truly valuable solutions might be found in such thinking? More on that in a later post!

Conclusion

We’re surrounded in our daily lives by things that are the way they are for where were originally good reasons – things beholden to the historical conditions under which they were designed. Changes in technology create the new possibilities for making those inherited conditions anachronistic and there’s often vast amounts of potential value-add yet to be discovered in those creative, unexplored spaces.

The ability of VR to create imagined worlds that are unconstrained from physical limitations gives us access to many new opportunities to destroy that historical link to previous conditions. We’ve built our company around the notion that this is definitely true for how we interact with medical images. What new ways of solving problems can you imagine in a world of your creation?

– Justin Sutherland